Construction practices prior to the 1970’s were not as defined and regulated as those developed in the 1980’s going forward. Western Engineering has building and construction codes from the early 1900’s to today in its reference library. During the 1980’s, the United States suffered from it’s most significant energy crisis with gasoline and other fuel prices skyrocketing along with the shortage of hydrocarbon fuels. Due to this shortage, buildings were built more tight in order to be more energy efficient. Prior to this, many buildings were more drafty, allowing release of hot air and moisture. The more current designs of buildings relied upon central Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning (HVAC) through ducting. Today’s “tighter” buildings had to be further designed to shed moisture through exhaust and weatherproofing practices such as vapor barriers, insulation, flashing and weeps and drains around the building’s exterior.

In much of the arid West, condensation only becomes a significant problem during the winter and early spring heating season. When warm air is laden with even small amounts of moisture or humidity, it will condense on colder surfaces. A psychrometric chart provides the dew point temperature based on the humidity level in the air, and can be used to help evaluate potential condensation problems. When condensation occurs, the resulting water can pose two major hazards: (1) water damage with or without mold growth, or (2) freeze-thaw cycles that can cause expansion and contraction, splitting or cracking building materials. The water or condensation forms a microclimate in the building envelope and the problem may not become apparent until significant damage occurs.

Home-Cost 2011

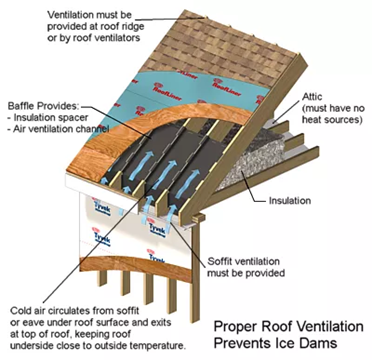

Figure 1 – Ventilation System that Prevents Condensation

One of the microclimate events may occur in a warm attic during the winter, sometimes causing ice damming https://www.werc.com/ice-dam-prevention-its-not-just-pretty-icicles/ In a warm attic in winter, moisture from the interior of the house reaches the cold underside of the roof sheathing. Once there, the dew point is reached and condensation occurs. If sufficient condensation develops, then wood frames, rafters, roof sheathing and attic insulation can become wetted and subject to mold and rot, which may result in roof leakage. To avoid heat and moisture in the attic, the attic needs to be well insulated and have penetrations from the house below, such as recessed lights, sealed or “capped”. Also, the attic should be well ventilated through appropriately sized soffit, ridge and gable vents to promote cold air entry. Finally, moisture sources such as dryer vents and bathroom fans should be vented to the outside and not into the attic. It is also wise to utilize the bathroom exhaust fan while showering and the stove exhaust hood while boiling water or liquids. Humidifiers should be used sparingly in bedrooms or living rooms to prevent excess humidity within the home.

Figure 2- Under-roof sheathing – water stained (not mold)

Typically the most visible place where condensation occurs is on exterior windows. When the temperature on the inside of the glass dips below the dew point, condensation occurs. If you find condensation on windows covered by drapes, open the drapes to allow heated indoor air to flow along windows, increasing the temperature of the glass and reducing condensation. If these measures do not reduce condensation on windows, you may have an inefficient bathroom fan, too much moisture due to humidifier use, or a dryer vented to the interior. Homes with large numbers of plants can cause condensation due to the high indoor humidity.

Western Engineering is experienced with diagnosing condensation issues, and can assist with mold sampling and identification should water damage be suspected to have caused mold growth. For more information, please contact us at info@werc.com

Water vapor reaching a surface equal or under the dew point temperature causes condensation as shown above.